1930 жылдардың бірінші жартысындағы паспорттау жағдайындағы кеңестік қалдықтар

Ғылыми мақала

Қаралымдар: 254 / PDF жүктеулері: 103 / PDF жүктеулері: 8DOI:

https://doi.org/10.32523/3080-129X-2025-151-2-64-80Түйін сөздер:

жұмысқа шығу, қоныс аударушылар, еңбек жұмылдыру, паспорттандыру, паспорт, арнайы рұқсатты аймақтар, ашық аумақтар, индустриализация, урбанизацияАңдатпа

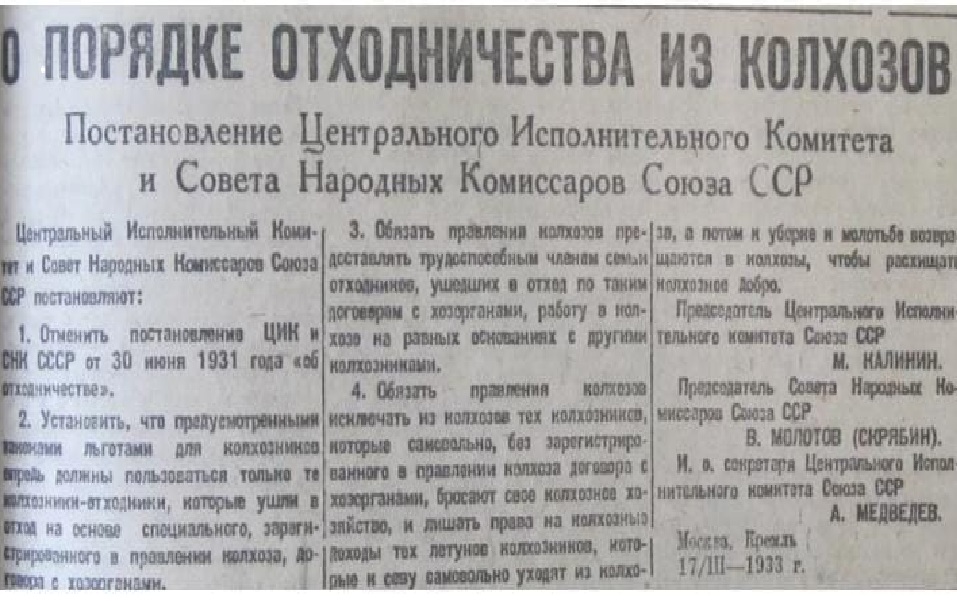

Мақаланың мақсаты – 1930 жылдардың бірінші жартысында, КСРО-ға төлқұжат режимін енгізу кезеңінде ресейлік ауыл үшін дәстүрлі құбылыс-қалдықтарды, ауыл тұрғындарының тұрақты тұратын жерлерінен уақытша ақша табу үшін кетуін зерттеу. Ғылыми жұмыстың міндеті 1930 жылдардың бірінші жартысындағы қалдықтардың өзгеруін көрсету, сондай-ақ паспорттық жүйенің енгізілуін және оның кеңестік өнеркәсіпте жұмыс істегісі келетін қалдықтарды паспорттаудағы рөлін талдау. Зерттеудің өзектілігі мен жаңалығы дереккөздерді терең сыни талдауда көрінеді, олардың кейбіреулері алғаш рет ғылыми айналымға енгізіледі, сондай-ақ паспорттау кезеңінде, соның ішінде ауыл тұрғындарына төлқұжат беру арқылы қалдықтарды реттеу механизмін қалпына келтіру мақсатын да көзделді. Зерттеу нәтижелері Кеңес үкіметі 1920 жылдар бойы жұмыссыздықтың өсу себептерін және қалалардағы әлеуметтік-экономикалық жағдайдың нашарлауын көре отырып, ауыл тұрғындарының стихиялық қозғалысын шектеуге тырысқанын көрсетті. Ел ішіндегі реттелмейтін қозғалыстармен күресу және өнеркәсіпті еңбек кадрларымен біркелкі қамтамасыз ету үшін мемлекет экономикалық жиынтықтар жүйесін енгізуге жүгінді. Алайда, 1920-1930 жылдардың басында жұмыссыздық "кадр тапшылығымен" алмастырылды және еңбекке деген сұраныс алғаш рет оның ұсынысынан асып түсті, бұл өсіп келе жатқан өнеркәсіпті кадрлармен қамтамасыз ету үшін биліктен жаңа шараларды талап етті. Сондықтан, паспорттау науқаны басталғанға дейін ауылдан жұмыс күшін жалдаудың екі арнасы – шаруа қожалықтары мен қалдықтар сақталды, бірақ шаруа қожалықтарымен келісімшарт жасасқан шаруалар үшін оларды қалдықтарға тарту мақсатында ауылшаруашылық жеңілдіктері енгізілді. Сонымен қатар, большевиктердің ауылда жүргізіп жатқан саясаты мен ашаршылықтың басталуына байланысты ауылдардан халықтың жаппай кетуі проблемасы күшейе түсті, бұл тауарлармен қамтамасыз етудің үзілуіне әкеліп соқтырды, тұрғын үй-тұрмыстық дағдарысты күшейтті, қалаларда қылмыстық қылмыстың өсуіне әкелді. Іс қағаздарында мұндай қоныс аударушылар еңбек көші-қонына қатысы болмаса да, қалдықтар деп аталды. Шаруалардың қашып кетуі жағдайында мемлекет ауыл тұрғындарын ауылдарда ұстауға және паспортты енгізу арқылы қалаларды әлеуметтік тазартуға бағытталған шаралар қабылдады – бұл қалаларда, әсіресе режимдерде тұру құқығын беретін сүзгі түрі. Ауыл тұрғындарына жаңа құжаттар берілмеді, бұл олардың бүкіл ел бойынша қозғалу мүмкіндігін шектеді. Енді ауылдан кету үшін шаруа өндірісте, мекемелерде, мектепте "қоғамдық пайдалы еңбекпен" айналысуға ниетін растайтын құжаттарды ұсынуға міндеттенді, мұндай ресми қағаздарға жұмысқа шақыру, жалдау туралы шарт, колхоз басқармасының қалдықтар туралы анықтамасы және т. б. кірді. Паспорт жүйесін енгізу іс жүзінде қалдықтардың стихиялық еңбек көші-қонынан индустриялық саланы ұйымдасқан жабдықтау жүйесіне ауысуына әкелді, ал ауылдан жаппай қоныс аударуға жаңа режимді бұзушыларға әкімшілік және репрессиялық шаралар қолдану қаупі төніп тұрды.

Downloads

Әдебиеттер тізімі

Baiburin A. The Soviet passport: History ‒ structure ‒ practices. Saint Petersburg: EUSPb. 2017. 488 р.

Vdovin А., Drobizhev V. The growth of the working class: 1917-1940. Moscow: Mysl. 1976. 264 р

Famine in the USSR. 1929-1934. In 3 volumes. Vol. 1. Book 2. Moscow: MFD. 2011. 656 р.

Kessler H. Collectivization and flight from the countryside are socio-economic indicators. 1929-1939. 1n: Economic History. The review. Moscow. 2003. Is. 9. pp. 77-79..

Kondrashin V., Mozokhin O. MTS political departments in 1933-1934. Moscow: Russian Book. 2017. 397 p.

Moiseenko V. The departure of the rural population to work in the USSR in the 1920s. Population. 2017. No.3(77), рр.53‒54. http://10.26653/1561-7785-2017-3-4

Popov V. Passport system in the USSR (1932-1976). Sociological research. 1995. No.8, рр.3−14.

Popov V. The passport system of Soviet serfdom. Novy Mir. 1996. No.6, рр.185−203.

Potapova N. State regulation of otkhodnichestvo in the 1920s. (based on materials from Siberia Historical Courier. 2023. No.1(27), рр.178−185. URL: http://istkurier.ru/data/2023/ISTKURIER-2023-1-14.pdf DOI: https://doi.org/10.31518/2618-9100-2023-1-14

The history of industrialization of the USSR 1926-1941. Documents and materials. In 4 books. Book 1. 1926-1928. Moscow: Nauka Publ. 2005. 838 р.

The national economy of the USSR for 70 years: Jubilee statistical Yearbook. Goskomstat of the USSR. Moscow: Finance and Statistics. 1987. 766 p.

The Soviet village through the eyes of the CHEKA‒OGPU‒NKVD. 1918-1939. Documents and materials. In 4 volumes. Vol. 3. Book 2. Moscow: ROSSPEN. 2005. 838 p.

Chernolutskaya E. Forced migration in the Soviet Far East in the 1920s and 1950s Vladivostok: Dalnauka. 2011. 511 p.

Fitzpatrick S. " Attribution to class" as a system of social identification. Russia and the Modern World. 2003. No.2, pp.133-151.

Shirer D . Stalin's Military Socialism: Repression and Public Order in the Soviet Union, 1924-1953. Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2014. 541 p.

Жарияланды

Журналдың саны

Бөлім

Лицензия

Авторлық құқық (c) 2025 Н. Потапова

Бұл жұмыс Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Дүние жүзінде.